The concert at the Festspielhaus Baden-Baden was a highlight throughout: Jaroussky and Lezhneva, I Barocchisti and Diego Fasolis with a showcase of works by Pergolesi and Vivaldi left nothing to wish for.

by Lankin

Antonio Vivaldi:

Sinfonia for strings and Basso continuo B minor, “Al Santo Sepolcro,” RV 169

Concerto grosso for two violins, violoncello, strings and Basso continuo D minor, “L’Estro Armonico”, op. 3 Nr. 11, RV 565

Nisi Dominus, Psalm 126 for alto solo and strings RV 608*

Giovanni Battista Pergolesi:

Stabat Mater F minor for soprano, alto, strings and Basso continuo

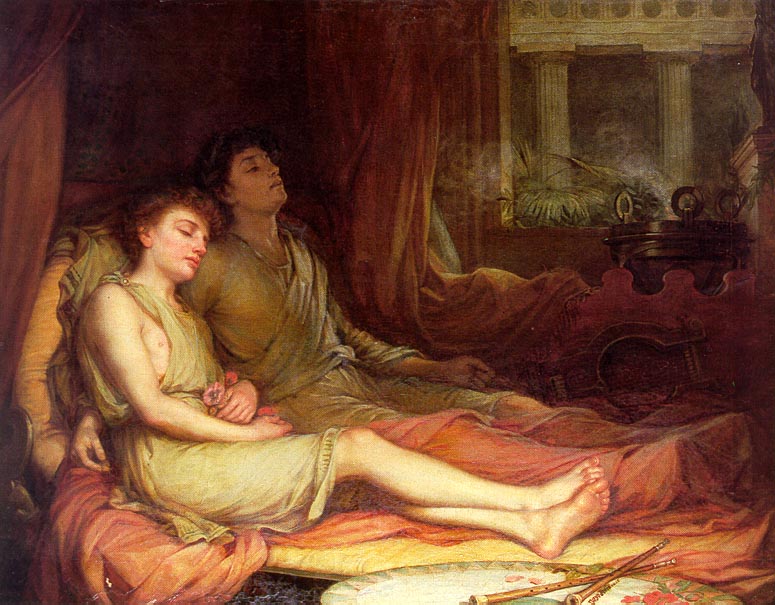

The programme was composed out of pieces by Vivaldi and Pergolesi. Starting out with two famous instrumental pieces by Vivaldi, the first half concluded with Vivaldi’s “Nisi Dominus.” The second half solely comprised of Pergolesi’s “Stabat Mater”; the “Salve Regina” by Domenico Scarlatti was chosen as an encore to finish off the evening. The piece is delightful, and it has many parallels to Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater – I suppose that this was the reason it was picked. The two centre pieces, the “Nisi Dominus,” and the “Stabat Mater,” correspond in a strange way. Both have their axis around which everything seems to be gravitating, like the eye of a storm or the black hole centre of a galaxy. For the “Nisi Dominus,” it is the “Cum dederit” (“For so He giveth His beloved sleep”), in the case of the “Stabat Mater,” it is the “Quando corpus morietur” (“While my body here decays”). Sleep, and death – they happen to be brothers in Greek mythology, Hypnos and Thanatos.

Hypnos and Thanatos, John William Waterhouse

I want to start my review with the second half of the programme, the “Stabat Mater.” Recently, a recording has been published with the exact same cast, and the CD is a marvel. It has been awarded a few prizes already, but it still hasn’t got the recognition it deserves, according to my own opinion. However, I rest assured that it will prove one of the legendary recordings of the piece in the times to come. Unique voices, great musicianship, and splendid recording and mastering combine to make it an absolute must-have.

I had heard the “Stabat Mater” with the same soloists, ensemble, and conductor (the same as on CD) in Neumarkt already about a year ago, and I was fascinated how the piece had evolved. It’s like seeing good friends over the years, or couples, who grow in their empathy and understanding for each other. Their communication becomes more and more subtle. The rendition was just like that: It was less outwardly dramatic than the one I heard earlier, most noticeable in the “Cuius animam.” Great praise goes to Diego Fasolis here. I will never tire of watching him live, in parts, as it is a clashing contrast to the sound he manages to produce with his equally splendid ensemble, I Barocchisti. There is never a second where it is in question that what he is doing there is in fact hard work. There is little fun, and much toil going on; he appears to be highly concentrated at all times. Concerning that especially the “Stabat Mater” is a piece most musicians can literally play by heart with their eyes closed, this is really outstanding. Mr. Fasolis wants to tell something; he wants more than humanely possible, and never tires. You can hear it, but it’s great to see it too once in a while. In contrast, the sound he and his ensemble produces doesn’t sound like hard work, and has nothing bookish or calculating to it. It’s living, it’s breathing, it’s flowing, … in short: It’s wonderful. If you have any chance, go and hear him and I Barocchisti live. There is more to it accompanying someone than just ripping off a great interpretation. Fasolis conducting gave the voices room to evolve, supported them, and created margin for dynamics. At no time did the orchestra plaster over the singers or seemed to restrain them. So despite the utmost discipline that Fasolis is airing at all times, or maybe because of it, the way he and his dream-team renders the “Stabat Mater” is clearly the most sensitive, freely-sounding interpretation of the piece I have ever heard.

As a matter of courtesy and of alphabetical order, I want to continue with Julia Lezhneva. Her voice has evolved a great deal over the past year, I find. It’s even heavier now, and has been called more operatic. I agree, but nevertheless it has lost none of it’s charm, its purity of attack like a perfect instrument. Lezhneva has a unique, instantly recognizable voice. In the age of quickly-replaced stars, this means a lot. It is always a treat to hear her sing.

Philippe Jaroussky had the major part that evening. The first vocal section of the programme was his alone. The “Nisi Dominus,” Vivaldi’s Psalm setting, can be called a standard in his repertoire. I was very curious nonetheless, and I wasn’t disappointed. Before, I had heard it live with his own ensemble, the Ensemble Artaserse, and of course I have his recording with Jean-Christophe Spinosi. This evening, it was different. The “Cum dederit” (“For so He giveth His beloved sleep”) is maybe the one piece in the “Nisi Dominus” most suitable for highlighting the differences. The basis of this ethereal piece is almost like a heartbeat and well, every person’s heartbeat is different. The art in this piece is to find a joint one between the conductor/ensemble and the singer. Very simply speaking: If it doesn’t match, it will in the best case be boring, and in the worst case, the singer will suffer. Fasolis’ version didn’t start out as mesmerizingly slow as Spinosi’s in my perception, but he slowed the tempo a little towards the end, at all times intensely focussed on and corresponding with Jaroussky’s singing. The sound of the violins he chose was altogether different from Spinosi’s – warm, and pulsing. A wonderful rendition; I very much regret that the broadcast from Amsterdam was cancelled.

This is maybe the proper place to mention the soloists and the ensemble yet another time, specifically Fiorenza De Donatis at the solo violin who played with great virtuosity and a wonderful sound.

When I first saw the announcement that Jaroussky was going to sing the “Stabat Mater” I wasn’t too excited. There are various recordings around on Youtube with different conductors, and I didn’t like any of them much. With Fasolis, however, it is as if he was been given wings. His phrasing is always sublime, but “Quae moerebat” took it to another dimension. While Fasolis and Lezhneva always appear concentrated in the way athletes are before their all-deciding run, Jaroussky makes everything appear effort- and weightless the moment he starts to sing. There’s a song called “Every little thing (s)he does is magic” – and in his case, that’s the plain truth.

Jaroussky is a wonderful duet partner, or as Lezhneva put it – “He’s the best.” It’s impossible to decide which pieces I enjoyed most, but “Inflammatus et accensus” as well as “Cuius animam” and “Quae moerebat” are always among my favourites. On a very personal note: Jaroussky even achieved to make me fall in love again with the “Fac ut portem” I had really been sick of before I heard his interpretation. Vocally, both singers were in terrific shape that night, and in total there seemed to be a good chemistry between them.

Sidenotes And Why PJ Is A Pristine Gem Of Mankind

This time, there was a signing session afterwards, and it was set up in a way that people had to pass Mr. Fasolis and Ms. Lezhneva to get their audience with Jaroussky. Even if the latter was clearly the most wooed that night, his colleagues didn’t seem to mind, and they were close enough to join the conversation. In hindsight, I regret not having brought flowers for Lezhneva and Fasolis after all. My sensibility got the upper hand, concerning they had to leave the next day the latest for Amsterdam, and I wanted to spare them the trouble of disposing of the burden of yet more flowers.

PJ was the kindest, most charming person ever. He tends to be that, yes, but that night he surpassed himself in random acts of kindness. Due to a series of adversary circumstances, my best friend had missed her flight in Barcelona, so she didn’t make it to the concert in time. I told PJ and he left her the cutest voicemail ever. The burden of gratitude I’m feeling in front of PJ is getting bigger and bigger each time. However, I could just-so restrain myself to not force-hug him, but only by scraping up the remnants of my Prussian discipline.

A few words about the audience: The coughing fits at the Concertgebouw have been mentioned, but believe me, you haven’t heard nothing yet if you haven’t been to Baden-Baden. Occasionally, I had the feeling of being inside a Tuberculosis quarantine station instead of a concert between the pieces. The circumstance makes it astounding that the audience really managed to hold it back during the music. I hope no one was close to asphyxiation. In seriousness, in case you were there, and were bravely coughing mostly-only during the breaks – get well soon!

The audience in Baden-Baden is very varied, depending on the performance. This time, it was considerably younger on average than when I heard Jaroussky with La Lemieux there. About a third stood up in the end, I would guess, which is already the peak I have ever encountered in Baden-Baden in total. Well, shuffling in the seats in excitement is the Baden-Baden way of a standing ovation, I would guess. Others might have completely different experiences; as I said before, the audience varies a lot there from performance to performance. In parts, it might have to do with the fact that the evening comprised of sacred works. Moreover, the sheer mass of people queuing for the signing later made it clear that the lack of standing ovation didn’t have any deeper meaning or was a sign of disregard in the slightest.

More pictures: [x]

Pet Peeve Of The Day

My ticket announced “Pergolsesi.” So I have a “Nisi Dominu” from Stuttgart now as well as a “Pergolsesi” from Baden-Baden. Really, guys, it’s not that hard to get someone to proofread, or is it? (And this is the proper place to say thank you, Kris!) [[Most welcome, ‘boo]]

***

Well, that’s it about this day. Actually, I had started out completely different. Firstly, I wanted to write something about the piece itself, as it means a lot to me. As it got rather lengthy, I decided to put it towards the end to make it simpler to just light-heartedly skip it. Anyhow, here it is. To all the others, thank you for your patience.

Let’s get serious … The “Stabat Mater” …

Now how do I even begin… It’s not only a classic, one of the most popular repertoire pieces in the sector of sacred music, by its work history alone it is unique. Almost everyone has heard that Pergolesi died shortly after he wrote it; an untimely and painful death – he was only 26. So just as for the Mozart Requiem, this of course adds to the mystery woven around the piece (even if Pergolesi wasn’t as dramatic to pass out of view on ascending steps to heaven.)

The composition, more so than his operatic works – here especially ‘La serva padrona’ deserves a mention – made him truly immortal. I don’t know if his soul found peace in the glory of the afterlife, but with the piece he exalted himself and justified himself as one of the truly great composers once and forever.

To say the piece was popular would be an understatement – almost every alto or soprano has sung it, and, subsequently, there is an abundance of recordings. There are recordings with boy sopranos, countertenors, women, and it never seems to get less popular. Well, justly, as it is amazing.

The Words

Despite its language being Latin, the “Stabat Mater” is very folk-like in a way. It always reminds me of the German Christmas-carol “Maria durch ein Dornwald ging.” The German lines are “Christi Mutter stand mit Schmerzen / an dem Kreuz und weint von Herzen / als ihr lieber Sohn da hing,” in English it is “At the Cross her station keeping / stood the mournful Mother weeping / close to her Son to the last.“ In whatever language, the words almost fulfil every criteria of Kitsch. The text is unspecific, it is using many emotionalized words – weeping, trembling, crying – all with the purpose of connecting the one who speaks with the action in a very immediate way.

What is particularly interesting is the perspective, because it is changing from verse to verse, it’s like a responsorium. There are merely observational ones:

“Stabat mater dolorosa …”

“Quae moerebat …”

There are verses which address the audience:

“Quis est homo qui non fleret?”

And there are those that are a direct prayer, a plea to god, or the Virgin Mary.

“Inflammatus et accensus …”

“Quando corpus morietur …”

Basically, all the ones with “fac” [fa:k] in it. Make me … make that I … Let me …

So in this alone lies a variety of perspectives. But of course we have more than just that, we have two voices, and so, necessarily, two points of view. In an attempt to put it simple: It’s like if you have one grid, and another, and you crosshatch them, and all of a sudden you have a variety of patterns that are forever new.

The Music

Pergolesi’s music is lush, is intuitive, it’s sensual. He sticks to the folk-like approach in parts, but his music doesn’t stay on the surface. His setting is very onomatopoetic almost, with trills on the “trembles,” piercing high notes at the “pertransivit gladius” to visualize the sword of judgement. Some pieces are almost weird. First of all, the “Quae moerebat.” (“Christ above in torment hangs”) When you listen to it, you can hear the inner turmoil, you can hear the sobs and cries – but you rather hear excitement than suffering. If you’re a musician – try and sing the piece in minor. Weird, isn’t it? It works quite well, so why did Pergolesi write this as an almost manic, frantic piece of excitement? But I digress …

In my defense: It’s very easy to digress with the Stabat Mater. Just two more digressions I find necessary: One is concerning the perspective, again, and one is concerning what Stabat Mater has to tell to an atheist.

Contemplation And Voyeurism

Catholicism can be quite … interesting. This is my outsider’s view. Let’s take a look at St. Sebastian to highlight what I mean. (Just as an alternative to the theme of St. Therese.)

St. Sebastian, sculpture by Antonio Giorgetti, at San Sebastiano fuori le mura, Rome, photography by Angela Bonilla

I wouldn’t mind spending much time in contemplation. There are a lot of examples of ecstasy depicted in Catholic art. Ecstasy, and suffering. Churches can be quite explicit:

Lorenzkirche, Nürnberg

In the “Stabat Mater”, the one who prays joins virgin Mary at the cross. This, but also the one who prays is witnessing the events, which is just a more noble word for watching. Agreed, it’s much the same as looking at a crucifix, but it enhances and drags out the experience. That is one layer. Now there is the next. When we listen, we aren’t praying as such. We are watching or listening to someone pray. Or we take their place when we identify. It’s up to us if we are mentally putting us into the place of suffering Christ, of the virgin Mary, if we join the ones praying, or if we are staying out of this in total and just admire the whole construct. Empathy is an act of mirroring another’s emotions, and the “Stabat Mater” makes it easy to get lost in a veritable Galerie des Glaces.

I have to bring in Therese here anyhow. You might be familiar with Bernini’s masterpiece of the Ecstasy of St. Therese. One thing that almost goes unnoticed are the witnesses depicted, because next to the centre sculpture, there is a little alcove with the spectators – witnesses, I wanted to say, watching Therese writhing in ecstasy. That the alcove is made to look like a theatre box is not a coincidence. We’re watching the watchers.

picture source: [x]

Back to the “Stabat Mater:” The great thing about the varying perspectives is that they enable the listener to change between them, like taking a dive; as deep as you feel brave enough to go. Just in the end, there is no way out. I think very few can detach the thought of death from their own person.

What The Stabat Mater Has To Tell To An Atheist

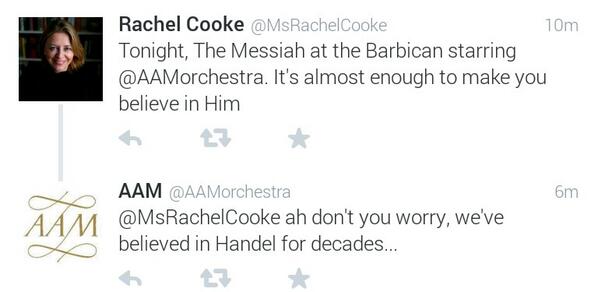

A few months ago, this gem was to be found on twitter:

I have to say, it voiced my heart-felt opinion there. However, the serious question is … Is it necessary to be a Christian to credibly sing sacred pieces? Let’s take a moment, as if you have even considered this question for a moment – as I have – it shows the topic is not as simple as it sounds. I am just bringing this up because Mr. Jaroussky once mentioned in an interview that he was in fact an atheist. As I will try to highlight, this needn’t be a drawback whatsoever.

To start with, sacred music is entirely different from secular works. To my knowledge, no one ever demanded when casting a Violetta that she had work-experience as a call-girl, and was suffering from an incurable disease to be able to properly identify or credibly portray the role. And of course, no one demands an Elvira to be a Puritan to sing in I Puritani.

It seems that with sacred music, we don’t condone the presence of a mask so easily. Sacred is about truth, not about roles. The grey zone there are the Passions, of course, where the personnage is given voices. (Random fact: At folk-like Passion plays, almost always an “outsider” from another village was cast as Judas. No villager wanted to play the role; it would have been a stain that would have been a handicap in their social lives otherwise.)

In short: Sacred music is about truth. Now where is the truth to be found in the Stabat Mater for an atheist? Which leads me directly to …

The Issues I Am Having With The Piece

The Stabat Mater can be seen as a glorification of suffering. At any rate, it is a contemplation of suffering. Of course, we can’t just go there and fight the Romans and take Jesus down from the cross, we’re doomed to passivity. The one we demand action from is the one suffering herself, and we demand something for ourselves. “Fac, ut portem, … fac ut ardeat … .” The piece – and the Catholic doctrine – tells us to be patient, to be passive. Suffering ennobles, and the purgatory burns the sins for those who haven’t suffered on earth enough already. To which abstruse conclusions this thought can lead can be easily highlighted at the case of Mother Theresa, withholding medical help and pain relief from people to make them suffer the more. When suffering is seen to be better than lack of suffering, it is crossing the line to the perverse.

Mary is a mother whose son is taken to die for the Greater Good. Tucholsky’s “Der Graben” immediately comes to mind and many other songs written in war times.

One of my favourite Pietàs is the one by Bouguereau:

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Pietà, Wikimedia Commons

It is almost overly realistic, and at the same time iconic (the composition, the halo, etc..). This polarity is very much like the one in Pergolesi’s work, very much like the recording even in fact. It’s all about how to render an icon life-like. There’s a difference between Bouguereau and Pergolesi, of course, given by what can be described as the limits of the respective style. However, the concept remains the same.

Bouguereau’s painting also conveys a message. Bouguereau was a trickster – a very clever man. Quite early on, he discovered that he could paint the most socially critically things as long as he covered them nicely in symbolisms and mythology. If you look at the picture, you can see the suffering, the torture she has been through in her face. There is no happiness whatsoever, no relief, no hope, just the defiance of not being able to understand why her son had to die. Unlike Michelangelo’s Pietà, she faces the viewer. It’s our fault, the glance says. She doesn’t accuse us, she just knows.

(When you look at The Madonna of the Lilies by the same painter, the differences and similarities are striking. She doesn’t face the viewer then, she has her glance averted.)

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, La Vierge au lys, Wikimedia Commons

The fault in the system that causes the suffering is intrinsic. It’s in us, in our society, in hierarchies. Yes, Mr. Bouguereau , that’s just how it is, how every soldier dies, how martyrs die up to the present day. We are rolling our eyes at Islamistic martyrs who believe they will go to paradise, but we fold our hands and pray for “paradisi gloria”? Am I the only one who feels a little queasy with that or who ever noticed any parallel? The promise of paradise is no comfort for Bouguereau’s Pietà, as it hardly is for a modern person.

Now, is Bourgereau’s Pietà in any way less truthful, less deep as, e. g., Annibale Carracci’s?

Annibale Carracci, Pietà

Basically, as an atheist, it is just like Bouguereau’s pietà. There are things that cannot be understood, that won’t be mollified with any excuse that the suffering happens for a reason or for the greater good. Nothing but suffering remains, and the “Quando corpus morietur” remains a death fantasy. There is no salvation to be found, only the silence after the last chord has been played.

Just a sidenote: Jesus isn’t only someone’s child, he is quite many people’s close friend. There is another Mary at the cross, of course: Mary Magdalena. This is her point of view, from Pergolesi’s almost-contemporary, Caldara. (The composers died in the same year, 1736.) I like the similarities and the differences between the two pieces. The piece, “In lagrime stemprato,” is sung by Maria Cristina Kiehr.

You don’t have to be a mother to understand what loss means, or empathy. Just as well, I don’t think you have to be a Catholic to render a sacred piece from the bottom of your heart. There will just be less comfort in the interpretations of the ones not quite convinced of “paradisi gloria.”

Your writing is very enlightening. No one can review the concert better and more accurately than you !! You gave me broad and deeper perspectives in listening the Pergolesi. I understand that you are copy writer. I hope

your writing is highly appreciated in the industry. I hope Philippe has opportunity to read your review/article about his concerts and CD.

I have never been to “French Melodies” concert. I thought I wouldn’t enjoy it as much as the other program

because I don’t know French at all therefore I cannot fully appreciate the delicate/entwined French poems. However there are only two “French Melodies” concerts

in next April when I can take vacation. It might be “Opium II “.

Thank you for your kind words! I will hear Opium in Neumarkt – very excited already!