As ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren… After Barcelona, São Paulo and Paris, on the 15th of April 2015, Philippe Jaroussky brought Verlaine to the small town of Neumarkt in Frankonia, bestowing on us a golden evening.

– by Lankin –

One word beforehand: usually I set out to write my reviews quite factually, but this time I desperately failed. However, professional reviewers seemed to face the same problem; they resorted to words like “séance” and “brain-melting”. So please bear with me, and do buy the album: it is fantastic. Here is the album trailer:

Yet another note: This piece got long. Here’s a link to the actual review for easy skipping.

Green and Verlaine

It is impossible to talk about the music on the album without adding a few words about Verlaine. Since I heard Green, I find it nearly impossible to separate the music he inspired from the poet himself, just as it is hard to separate Paul Verlaine from Arthur Rimbaud’s influence on him.

Verlaine marks the dividing line between Romanticism and the Symbolist movement, and was a driving force in the creation of the genre of word-music – poems set to music. The album Green strives to show a significant cross-section of works all sparked into existence by Verlaine’s oeuvre, by more than just the usual suspects.

For myself, there is a lot to delve into yet on the Green album, mainly because every piece gives reason to discover, or rediscover, Verlaine’s poems, and because of the joy (and delightful pastime) of comparing them to other poets’ works on similar sujets. (Poems about “autumn” alone could probably fill volumes, from Shakespeare to Keats and Rilke.)

Green’s approach and aspirations are very similar to the Farinelli album in terms of music history. Yet on Green, there is another element: to have all these different works performed by the same outstanding singer and with this fabulous accompaniment is a rare privilege because it facilitates direct comparison. Yet there is more of Jaroussky in it: for some songs, Reynaldo Hahn’s Chanson d’automne among them, the Master himself provided the transcription for string quartet. There is also a special bis with Nathalie Stutzmann, Jules Massenet’s Rêvons c’est l’heure (La lune blanche), especially surprising and delightful to hear if one is familiar with the usual version for soprano/tenor, or mezzo-soprano/baritone. For comparison:

France Duval and Bruno Laplante:

And Nathalie Stutzmann and Philippe Jaroussky:

Jaroussky’s interpretations are sublime throughout. I have many many recordings of some of the same pieces dating back to Dame Nellie Melba, and among them all, his versions are easy favourites for me to pick. Verlaine, always wishing for naturalezza and purity himself, would have liked Jaroussky’s diction, his art of singing. A lot of heart, work and soul has gone specifically into this album and it doesn’t go unnoticed. By recording more than one composer’s version of a piece, Jaroussky shows analytic distance and the joy at switching perspectives. The results couldn’t be more contradictory.

“All theory, dear friend, is gray, but the golden tree of life springs ever green.”

(“Grau, teurer Freund, ist alle Theorie, und grün des Lebens goldner Baum.”)

Mephisto in Goethe’s Faust

To listen to the different settings, spanning from the poet’s contemporaries to chansonniers, is like a time-travel that affords a glimpse into different characters; it is astounding to which extent Verlaine’s words, apparently, are open to interpretation. Most striking, to me, was the comparison between Reynaldo Hahn’s and Charles Trenet’s Chanson d’automne. While Hahn centres on the spirit of rejection, the sense of abandonment, hostility and loneliness, Trenet spins off with delightful self-distance without ever becoming cynical. The way he sets words that, at their core, are devastating to easy-to-listen-to music is just as poignant as Groucho Marx singing Hello, I Must Be Going at a performance shortly before his death – a farewell with little melancholy, and without any bitterness.

There are more rewarding comparisons in the different compositions based on Prison, one of Verlaine’s most famous poems; Green features the versions by Déodat de Séverac, Reynaldo Hahn, and Gabriel Fauré. Prison is what the title states, a poem about a man imprisoned, watching the outside world as an onlooker without any chance to interact and filled with regrets. By the context in which it was written, it is comparable to Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis. Verlaine’s imprisonment was related to but not caused by the incident where he shot at and wounded Rimbaud, his lover at the time. Originally, Prison was dedicated to Rimbaud but the dedication seems to have been withdrawn to avoid new scandal.

Verlaine’s Catholicism

The time spent in prison gave Verlaine cause to reflect on many aspects of his life, and marked a turning point. He converted to Roman Catholicism; his Romances sans paroles (including the album-title-giving Green) were published in 1874, during the time of his imprisonment. Another poem written during his imprisonment, Crimen amoris, is dark, and drenched with symbolism.

While it is not part of the Green album in any way, I find the piece nearly indispensable for a better understanding of Verlaine. It is safe to say that his conversion didn’t result in him becoming a more content person, as reflected in his later collections and cycles – rather he seems more and more consumed by remorse, a topic that is already hinted at in Prison’s closing lines, “Dis, qu’as-tu fait, toi que voilà / De ta jeunesse?” (“Say, what have you done / with your youth?”)

To compare Rimbaud’s Vierge folle / L’époux infernal (The Foolish Virgin / The Infernal Bridegroom) from his Une saison en enfer (A Season in Hell) and Verlaine’s Crimen amoris also makes for a rewarding juxtaposition. Rimbaud exposes the dirty laundry; to some extent, it reads like a transcript from a reality show, or an angry chat-rant (albeit one in impeccable style.) Rimbaud takes the setting of a futile prayer, poking fun at – among other things – Verlaine’s Catholicism. Rimbaud isn’t going to just die, he satirises Verlaine: “Un jour peut-être il disparaîtra merveilleusement; mais il faut que je sache, s’il doit remonter à un ciel, que je voie un peu l’assomption de mon petit ami!” (“Some day maybe he’ll just disappear miraculously, but I absolutely must be told about it, I mean if he’s going to go back up into heaven or someplace, so that I can go and watch for just a minute the Assumption of my darling boy!”) (Translation via: [x])

However, Crimen amoris shows Rimbaud even fell short in his estimation of how highly Verlaine regarded him – Verlaine doesn’t only write of Rimbaud as a saint or saviour, but as of a dark angel, an adolescent demon, executing God’s will as he determines it to be. Conflicting as both versions are, they show Verlaine’s attempt to integrate Rimbaud into his new-found belief by transfiguring him and making him eternal. Hendecasyllabic throughout (eleven syllables on each phrase), Crimen amoris recalls ancient poetry, and it has the intensity of a vision.

“Oh ! je serai celui-là qui créera Dieu !”

[…]

La torche tombe de sa main éployée,

Et l’incendie alors hurla s’élevant,

Querelle énorme d’aigles rouges noyée

Au remous noir de la fumée et du vent.

“Oh! It is me who will create God!”

[…]

The torch fell from his outstretched hand,

and kindled the roaring blaze,

A monstrous war of red eagles that seemed to drown

In the black swirls of smoke and wind.

Most probably it is only me, but the poem makes me recall Revelation 16, 17-18:

“And the seventh angel poured out his vial into the air; and there came a great voice out of the temple of heaven, from the throne, saying, It is done. And there were voices, and thunders, and lightnings; and there was a great earthquake, such as was not since men were upon the earth, so mighty an earthquake, and so great.”

Verlaine’s conversion to Catholicism can and has been seen as an attempt of escape from the world, as were Rimbaud’s extensive travels. Yet maybe it was the symbolism that allured him above all, and a hunger for meaning and salvation that finally caused him to convert.

After Rimbaud, Verlaine fell in love once more, with Lucien Létinois, a pupil of his who was 17 at the time. When it became an affair, it was an incident that Verlaine deeply regretted. He distanced himself, but never stopped dearly loving the young man. In 1883, five years after they had met, Létinois died. The lines Verlaine wrote upon his death ring more personal, cynical and bitter than anything he had written before: “Mon fils est mort. J’adore, ô mon Dieu, votre loi. / Je vous offre les pleurs d’un cœur presque parjure…” (“My son is dead. I love, oh my God, your law. / I offer to you the cries of a heart close to perjury…”) It seems ironic that these words seem never to have been set to music.

At the same time, for me, the lines make me recall Rimbaud’s persiflage of Verlaine from Une saison en enfer: “Je suis au plus profond de l’abîme, et je ne sais plus prier.” (“I am in the depths of an abyss, and I have forgotten how to pray.”)

Back to Green

To listen to the album is like Plato’s cave parable in a way. Let’s say the Verlaine poem was absinthe. Green, 50 or 60 per cent and with that lovely greasy-sweet taste to it. The different settings are different glasses, breaking the light in different ways, so the fluid looks different each time. Jaroussky’s renditions add another level. Now you can’t take your eyes away from the hand that holds the glass, how it is held, how the fingers touch the surface. The absinthe might be delicious, the glass of questionable style, but it all becomes less important than the hand that holds it, and less than the smile while it is raised to the lips. (I am not good at metaphors, and this paragraph may serve as a proof.)

I have often heard of late that the repertoire on Green was somehow closer to the true self of Jaroussky than the Baroque repertoire he concentrated on before, and the album art may add to this impression. Now I have given this a bit of thought and I cautiously dare to disagree. Yes, he feels at home there, I can tell. Some pieces feel as immediate as any he has ever sung. His voice is always great, but in this repertoire it seems otherworldly. The sheer sound of his voice, live, was a jaw-dropper for me this time. The studio recording doesn’t even do him justice.

However, even with Verlaine – and in particular with Verlaine – it isn’t as if Jaroussky was speaking about his private self. The lyrical self might coincide with Verlaine in the majority of poems, but it surely doesn’t coincide with Jaroussky in most of the songs. There are tangential points, obviously, but it isn’t a one-to-one-alignment. (I do hope Mr Jaroussky never planned to raise a gun against a lover, and he certainly is nothing of the “vierge folle” Verlaine has been labelled as by Rimbaud.)

When I listen to some of Jaroussky’s recordings of Vivaldi, I have at last the same sense of immediacy that I have at Green. In song repertoire, the dividing line between artist and lyrical self is just more subtle because, unlike in an opera, there is no formal role dividing the two. On top of it, I think that slipping into an on-stage persona, not being oneself, might in fact enable a certain authenticity of sorts. When is Callas more Callas? In paparazzi pictures or when she sings D’amor sull’ali rosee? It is hard to tell, I think. The stage, roles and their characterisations allow artists to be what they usually aren’t (or most baritones and basses would be in jail).

Art is more than real life. It speaks of things that might yet be and could have been. Verlaine does the same in this respect as any opera does. For him his poems are his vehicle of expression. In real life, he was a whole lot different – aggressive at times, choleric, and weighed down by obligations. It was his art that allowed Verlaine to fly, and become bigger than his life.

Classical music, poetry, and fine arts are sublimation and refinement. (Metric measures, melody, harmonies is not what we generally use as means of expression in everyday life.) Yet that doesn’t make what is said any less immediate or true. I bet I wasn’t the only one who remembered the Osterspaziergang (The Easter Stroll, or Parade) from Goethe’s Faust at this year’s wonderful Easter morning. “From the ice they are freed, the stream and brook…” (“Vom Eise befreit sind Strom und Bäche / durch des Frühlings holden, belebenden Blick…”). Now, is this Faust speaking? Goethe speaking? The actor who happens to be on stage? It is the words that speak to us, crossing the boundaries between author, lyrical self or role, and ourselves, as if the lines were an object that exists in multiple universes and connects them.

“Always other to the way in which he was imagined… elusive, unfigurable …”

About Rimbaud as reflected in Verlaine’s drawings, from Crossed Drawings (Rimbaud, Verlaine and Some Others) Author(s): Alain Buisine and Madeleine Dobie, Yale French Studies

As personal as the Green album claims to be, the question teasingly put later in Fisch-Ton-Kan, “Qui je suis?” (“Who am I?”) hasn’t been answered; rather the album and more yet, the live concert added to the mystery this man is for me. He might perceive himself as close to Verlaine in spirit; for me, there are more similarities between him and Rimbaud, not because of the “perfectly oval face of a fallen angel” (“visage parfaitement ovale d’ange en exil”) – Verlaine – but for his elusiveness and the mystery that surrounds him despite all his public appearances. Just as Rimbaud, he probably has little idea to what heights he is idolized by some, or what he means to others.

“…les plus beaux yeux que j’ai vus – avec une expression de bravoure prete a tout sacrifier quand il etait serieux, d’une douceur enfantine, exquise, quand il riait, et presque toujours d’une profondeur et d’une tendresse etonnantes.”

(“… the most beautiful eyes I have ever seen – with an expression of gallantry, as if ready for all sacrifices, when he was serious, of exquisite, childlike gentleness when he smiled, and almost always of an astonishing depth and tenderness.”)

Ernest Delahaye about Rimbaud, from Manuscrit Casals, Bibliothèque litteraire Jacques Doucet, quoted in Delahaye témoin de Rimbaud

“Pas la couleur, rien que la nuance!” – The Translators’ Plight

Verlaine is an enchanter; he uses words for their sound, as a flatter and a caress. Together with the strict verse form of most of his poems, it is obvious why they make almost perfect material for basing music on them.

In my opinion, that Verlaine never quite achieved the popularity and status he has in France – named Prince of Poets during his lifetime and never waning in popularity there ever since – in other countries is because of the special way he uses language. His poems are like magic spells that once translated, lose a great deal of their power.

This one I find a perfect example; it is an excerpt from his poem Parsifal, first published in 1886, in the Revue Wagnérienne. It fits in well with Verlaine’s religiosity, summarising the plot but focusing on Amfortas’ suffering (brought about by fleshly sin) and his salvation by Parsifal, the chaste youth.

Parsifal a vaincu les Filles, leur gentil

Babil et la luxure amusante – et sa pente

Vers la Chair de garçon vierge que cela tente

D’aimer les seins légers et ce gentil babil;

[…]

I am just going to focus on one thing here, the “gentil babil”, the gentle babble or chatter of the girls, the little rhyme of “gentil” with “babil” enhancing its onomatopoetic quality. The phrase appears more than once, once as an enjambment (spanning two lines), reminding us of Poe’s Raven where the words finish and start the halves of the rhyme, “As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.” (Translators are having a hard time with this one too. For some examples, see German Wikipedia.)

Verlaine uses the enjambment and later repetition as a subtle way to show, not only to tell, the uncoordinated offbeat and gentle banter, not being part of Parsifal, a pleasant but unwanted background noise, its allure not succeeding in deterring him from his mission. So, how to render this in other languages…

Parsifal has overcome the gently babbling daughters

Who’d distract him to desire; despite fleshly delight

That might lure the virgin youth, the temptation

To love their swelling breasts and gentle babble;

(I wasn’t able to research the translator. Source: [x])

Parsifal has trounced the girls, their tender notes,

Their breasts, their gentle banter, and all the fancy

Turns that can provoke an untried youth to fancy

Their light breasts, their banter, and their gentle tones.

(John Turner)

Conquered the flower-maidens, and the wide embrace

Of their round proffered arms, that tempt the virgin boy;

Conquered the trickling of their babbling tongues; the coy

Back glances, and the mobile breasts of subtle grace;

(John Gray)

Let’s summarise: it is a problem, because at times the colour – rhyme scheme, meaning, atmosphere or metre – may be preserved, but Verlaine’s shades mostly are lost – and Verlaine’s poetry is suffering more than others because these little tricks in fact constitute a vast part of his art.

Finally – The Concert!

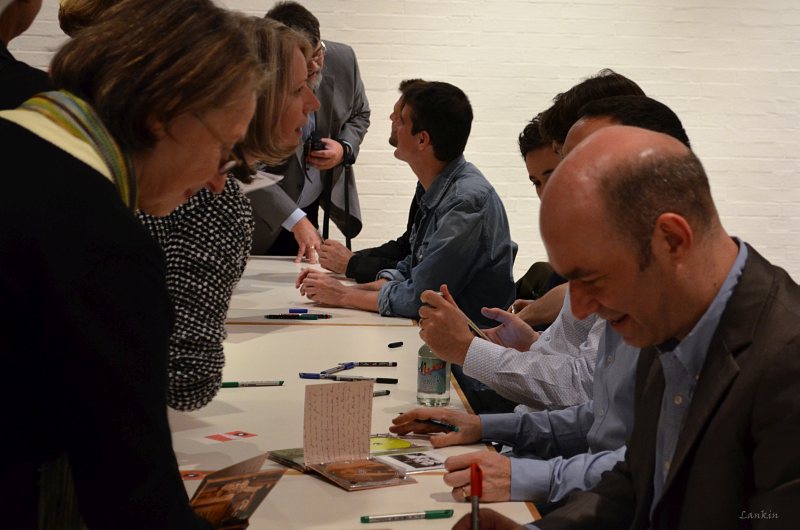

Concerts at Neumarkt are special. It’s a rare luxury to listen to performers of this prestige in a relatively small venue with about 500 seats. The events are made possible by the Konzertverein; patrons donate and fund the concerts that, on federal budget alone, wouldn’t be feasible. The venue is famous for its acoustic qualities. The Reitstadel is almost perfect for the kind of repertoire – it is big enough to flatter the performer so they feel relaxed, and at the same time is small enough to allow the singer to rest assured that their voice will carry to the last row even at the most subtle of pianos. At the same time, the acoustics benefit the clarity of the consonants, highly beneficial for a recital of songs that are centered on the words, and highlighting Jaroussky’s splendid diction in that case. The audience is much like at the Ansbacher Bachwoche – very appreciative, educated, and very disciplined.

“Attache-toi à nous avec ta voix impossible, ta voix ! unique flatteur de ce vil désespoir.”

(“Join us with your impossible voice, oh your voice! the one flatterer of this base despair.”)

Arthur Rimbaud, Illuminations

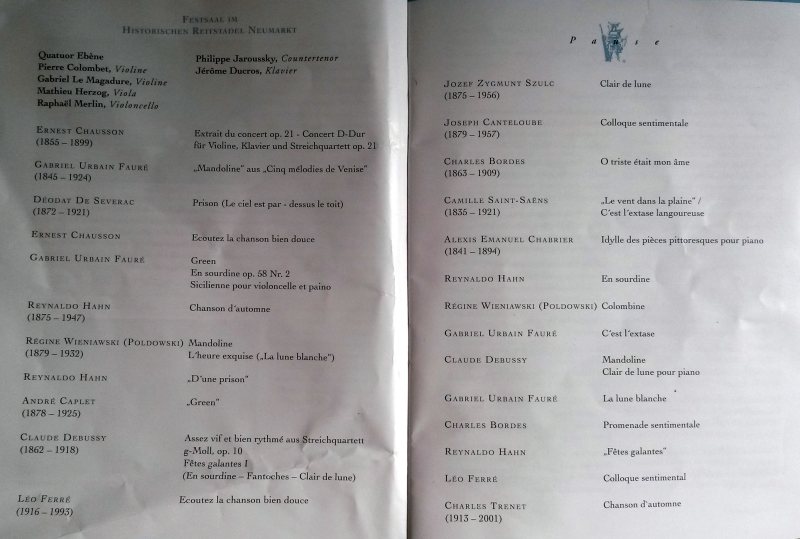

The programme that night mostly comprised a selection from Green. Jaroussky sang by heart, which increased the sense of immediacy, and was not a small feat considering there were almost 30 vocal pieces. He was accompanied by Jérôme Ducros on the piano and the Quatuor Ébène. The prestigious ensemble was very well steeped in the repertoire, and provided a great accompaniment – and once, a men’s chorus even. Jérôme Ducros is a masterful accompanist, especially in French repertoire. He seemed happy that night, and the connection with Jaroussky appeared to instant. However, I couldn’t help noticing that the quartet was perceptibly formal that night. It was the last or penultimate performance, I think, including Mathieu Herzog, a founding member of the Quatuor Ébène, on the viola, so maybe that was a factor causing them mostly to retreat to mere formality. However, it didn’t diminish the artistic performance in any way. As their solo pieces, the ensemble chose an extract from Ernest Chausson’s Concert Op.21 in D Major as an opener, then Gabriel Fauré’s Sicilienne pour violoncelle et piano, a movement from Claude Debussy’s String Quartet Op.10 in G Minor, Alexis Emanuel Chabrier’s Idylle des pièces pittoresques pour piano (played in an adaption for string quartet), and finally Claude Debussy’s Clair de Lune was sensitively executed by Jérôme Ducros.

The closing pieces of both halves were chansons, allowing the audience to applaud without regrets. I was entranced by the programme throughout, yet said chansons were my personal highlights of the evening. Never before had I heard Jaroussky sing a fortissimo with such self-abandon and apparent joy relishing in the sound of his own voice as in Ferré’s Ecoutez la chanson bien douce, the get-out-dance of part one of the programme that ushered the audience into the break slightly intoxicated. His ravishing and at the same time utterly innocent way of singing in this piece made me recall Rimbaud’s Romance:

[…] Nuit de juin ! Dix-sept ans ! – On se laisse griser.

La sève est du champagne et vous monte à la tête…

On divague ; on se sent aux lèvres un baiser

Qui palpite là, comme une petite bête… […]

You’re 17! In June! It gets you high —

The sap’s champagne: it makes your whole head ring . . .

You ramble — suddenly you feel a kiss

That flutters on your lips like a live thing

(Translation via WikiSource)

To listen to Jaroussky singing Ferré’s Colloque Sentimental live, for me, was like hearing Fritz Wunderlich sing Morgen by Richard Strauss. It felt like I never heard the song before, as if it was new and this was the one and only true rendition. I am still in absolute awe. The subtle shades he brought to the song were extraordinary; he added a new depth of feeling to the song. The simple suspended 4th at the first “leur paroles” became like a little shrug, the sinking arms of someone realising that the person he loves isn’t running towards them but is in fact going to embrace the person next to them. The otherwise out of place outbreak on “non!” that doesn’t even fit the original sense of the line in the poem where it is a careless side-remark, became an outcry of self-realisation, leaving the frame of the overheard talk in total. The moment he sang it, it felt right, and that this was how it was meant to be. For me, it was the closest to a transcendent experience a poor atheist soul like mine can ever get. I’m still recovering.

The messa di voces Jaroussky added to Charles Trénet’s Chanson d’automne were breathtaking, flawlessly executed on a seemingly endless exhale. They were a veritable show-stopper, the song of a nightingale. Nonetheless, I think there was more to it. It was as if he was saying “Is this what you rather want? You like it? I can do that, but it isn’t me, see?” He finished of with a wonderfully faltering “feuille morte,” the sole moment of irony and kitsch in the listed program, as well as if to highlight what he could do, but won’t. Yes, I plead guilty. I love baroque showpieces, and I love ironic self-distancing, at times. Now I am feeling moderately bad about it. Yet, it is as if Alan Rickman would call you and leave an unflattering voicemail message. While opposed to being insulted, you would probably still replay it, and revel in the sheer sound of his voice. The rest of the audience didn’t mind being mocked, as little as I did, but instead celebrated it with gracious applause. It didn’t end there.

The encores were wonderful, a great parting gift. The first, Fisch-Ton-Kan, from the operetta of the same name by Emmanuel Chabrier, is a witty and fast-paced showpiece. Fisch-Ton-Kan is the offspring of royalty, he says, and now he is forced by circumstances to juggle all over the world – even in Neumarkt, and we appreciated it. Probably irrelevant in the context, but I am adding it for the picture: Fisch-Ton-Kan was later attributed as a nickname to Napoleon III, the first elected president of France.

|

Advertisement for Pierre Vésinier: Les amours secrètes de Napoléon III (1883, 1884). Vésinier (1826-1909) was a fierce enemy of French emperor Napoléon III. Even 13 years after Napoléon was defeated he tried to mock him as politically cruel and morally depraved by this kind of chronique scandaleuse. Gallica hosts an incomplete version. Via [x] |

Fisch-Ton-Kan is a phonetic sound-alike to “fiche ton camp” (get lost), and this is intentional. Yet, we stubbornly stayed, and were rewarded with encore number two, Brassens’ Colombine. The obligatory baritone verse didn’t delight me as much as the whistling at the end. Both I didn’t so much perceive as a dropping of the pants than as a delightful little tease, an elaboration on the sujet of Que je suis?. However, we deeply appreciated these glimpses into Mr Jaroussky’s evasive private self. The evening concluded with Jaroussky whistling a D5 at perfect pitch. (Who would have doubted.)

Very personal, only slightly related to Mr Jaroussky

I arrived in Neumarkt with a lot of anticipation (train service had conspired against me that day), and a bad conscience – I wasn’t prepared as well as I would have wished to be; I didn’t get sheet music and really took in all the pieces I was going to hear. My parents joined me, which particularly made me happy. The last time we managed to go to a concert together was Tristan in Berlin, some 15 years back. My dad doesn’t like countertenors as such and isn’t too fond of French composers; in addition, he teased me, repeating he was missing Porto v Bayern München until I softly hit him over the head with the programme. After the concert, he was silent and repeatedly mumbled something about deep respect. I know that fond look in his eyes. He gets that when he becomes a granddad or when he hears Thielemann conduct Götterdämmerung (the latter is more likely to be repeated.)

And one last thing: many many thanks to David for his proofreading!

15 April 2015, Neumarkter Reitstadel

Philippe Jaroussky, countertenor

Jérôme Ducros, piano

Quatuor Ebène

Pierre Colombet, violin

Gabriel Le Magadure, violin

Mathieu Herzog, viola

Raphaēl Merlin, violoncello

El inglés es un idioma de mierda.les ruego ya no màs infligirme esta taradura en mi muro face book. Si Philippe tiene vergüenza de Francia, que nos lo diga. Pero por favorr ya no baveen màs en INGLISH! que me cae de muerte.

Unfortunately, I don’t have any means of influencing which post appear on your Facebook feed, and in which language. I have to disagree: English isn’t a language of shit, it is the language of Wilde and Shakespeare. Language is a tool, capable of different things. Some wield it like a paintbrush, and others as a weapon.

I deeply regret that I cannot (yet!) express myself in fluent Spanish but I would hesitate before dismissing the language of Cervantes, Calderon, Lope de Vega and Lorca as a “language of shit”!

… or Juana Inés de la Cruz! Thank you for your comment!

… who was quite a looker, btw! I think I’ve had a sense of humour by-pass as I find the original comment (from “Rippes”) crassly offensive on several levels.

She was! And well yes, the original comment had me resort to my personal anger management therapy before I answered, which is: googling “capybara” and switching to picture search.

I’m trying not to judge. If I came across such a juicy piece of text on Verlaine and Philippe and wasn’t able to fully grasp it maybe I’d be raving mad too and cursing every English speaker down to the Anglo-Saxons. Maybe.

Maybe. Probably not. ^^

Gerade habe ich – leider mit einigen Unterbrechungen – Deinen Artikel lesen dürfen. Zunächst einmal habe ich mich gefreut, daß er entgegen meinen Befürchtungen angesichts der Überschrift eben nicht auf Französisch war, weil das zu meinem großen Bedauern eine Sprache ich, mit der ich so gut wie gar nicht vertraut bin. Und ja, ich hatte eine zweite (und sogar eine dritte) Fremdsprache in der Schule, aber das war unter anderem Russisch (was mich übrigens zu der Frage bringt, ob der Sänger ‘Jaroussky’ nach einem russischen Ahn so heißt, ‘ja russki’ – ich bin Russe/aus Russland). Aber da schweife ich ab.

Ich hatte leider noch nicht das Vergnügen, auch nur eine Tonaufnahme von Herrn Jarousskys Kunst genießen zu dürfen. Ich liebe zwar gerade die instrumentalen Stücke französischer Komponisten der Romantik und des Symbolismus, auch Expressionisten, aber mit dem Gesang habe ich es eher nicht so. Was nicht heißen soll, daß ich es nicht würdigen könnte, wenn die Künstler ihre Kunst beherrschen, aber ein Teil der Würdigung lebt ja bekanntlich davon, Vergleiche ziehen zu können, und mangels Erfahrung kann ich diese Vergleiche eben nicht ziehen. Ich sollte wohl mal daran arbeiten.

Was mir besonders gefiel, war Deine Art, den Konzertabend einzuleiten und somit auch mir – angesichts meiner blinden Flecke – zu erlauben, eine Ahnung des Erlebnisses zu erhaschen. Mit Deinen Ausführungen hast Du für mich eine Verständnisgrundlage gelegt (Poesie gehört übrigens auch zu meinen blinden Flecken), ohne die ‘Verlaine’ und ‘Green’ nur inhaltslose Begriffe gewesen wären (von Rimbaud hatte ich sogar schon einmal – oberflächlich – gehört).

Sehr interessant und gut lesbar fand ich Deine Ausführungen zur Kunst als Überhöhung der Natur/der Wirklichkeit/des Lebens und zu der Frage nach dem Verhältnis zwischen ‘Lyrischem Ich’ und der Person des Interpreten. So klar und verständlich nachvollziehbar formuliert habe ich das bisher selten gesehen – und Kunsttheorie ist bei mir ausnahmsweise kein blinder Fleck.

Der Konzertbericht schließlich war so wunderbar emotional, daß ich tatsächlich eine Vorstellung davon bekam, was in Dir und den anderen Zuhörern vorging, und das ganz ohne es selbst gesehen oder gehört zu haben und ohne jegliches Vorwissen. Das halte ich selbst für große Kunst. Und da werde ich neidisch!

Herzlichen Dank, daß Du mich auf Deinen Artikel hingewiesen hast,

schöne Grüße von Bettina.

Danke danke danke! Huch, so eine Lobeshymne hätte ich jetzt nicht erwartet! *blushes* Oh und “ja russki’ – ich bin Russe/aus Russland” – genau, spot-on. So hat sich ein Vorfahre an der Grenze vorgestellt, und die haben das als Namen aufgeschrieben.

[…] Our own review; view full text at Philippe Jaroussky Completely Unofficial […]