A dream cast, a great orchestra, an ideal location, and a live-stream — there can never be too much of a good thing, or so they say, but the latest production of Julius Caesar of the Salzburger Pfingstfestspiele, got close to prove otherwise.

– by Lankin –

The evening was a succession of highlights; at times it was hard not to lose track of the whole. Bartoli, Scholl and Dumaux pulled off their parts with enormous skill, and tremendous routine; they had appeared countless times in their respective roles before this production. Anne Sofie von Otter and Philippe Jaroussky were outstanding; I am always impressed how much Jaroussky adapts to the vocal style of his partners, and in the case of von Otter, with a splendid result; this is especially important, as the duet is a vital part of both their roles, as it shows the emotional connection between the characters, their similarities and differences. Where Cornelia has only utter hopelessness to offer, Sesto adds the poignant edge of futile hope to it that only youth can have.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_profilepage&v=M4RSlu2nuDg

CORNELIA & SESTO

Son nata a lagrimar

Son nato a sospirar,

e il dolce mio conforto,

ah, sempre piangerò.

Se il fato ci tradì,

sereno e lieto dì

mai più sperar potrò.

Son nata…

*

I was born to weep

I was born to sigh,

And I shall mourn forever

My sweet consolation.

If fate has betrayed us,

I shall never again hope for

A serene or happy day.

I was born…

The cast

The cast was almost too great to be true. For easy reference, I will just add a listing here:

Giulio Cesare (Julius Caesar) – Andreas Scholl

Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt – Cecilia Bartoli

Tolomeo, her brother and husband (!), King of Egypt – Christophe Dumaux

Cornelia, widow of Pompey – Anne Sofie von Otter

Sesto, her stepson – Philippe Jaroussky

Achilla, Tolomeo’s General – Ruben Drole

Curio, a praetor, Caesar’s General – Peter Kálmán

Nireno, Cleopatra’s and Tolomeo’s servant – Jochen Kowalski

Il Giardino Armonico

Giovanni Antonini, Conductor

The main characters don’t really need an introduction, but I think I would mention the rest of the cast:

Ruben Drole in the role of Achilla was given a chance to introduce himself to the Salzburg audience by this production — his voice is almost too beautiful for an Achilla, who is mainly a brute. Jochen Kowalski’s achievements I won’t put in doubt: that night, however, he didn’t really render a good impression after all. I wished they would have left out his aria, because his acting skills were acceptable. The direct comparison with the other singers is bound to bring out the flaws rather than the strong points of his singing. However, I approve of him being cast there; it had the taste of a cameo appearance though — a glimpse of former lead roles of his, some good years past.

The opera

When the opera starts, Julius Caesar has just conquered Egypt. Cleopatra is supposed to be about 16 years old. Nevertheless, she is a queen, and she knows when her power is in danger. The Romans do not care much about Egyptian tradition, by which the succession via the female line is all that counts. Her brother (and husband!), Tolomeo, sees his chance: With Caesar as an ally, he might even keep some position, and power is what he craves. He thinks sending Caesar the head of a beheaded enemy, Pompey, will endear him. Caesar is not amused. Trouble ensues.

Pompey leaves behind his wife, Cornelia, and his son, Sesto. Tolomeo wants to degrade them, imprisoning Sesto and letting Cornelia work in the palace garden, and one doesn’t need to be particularly dirty minded to sense that he doesn’t have only flowers in mind.

Achilla, Tolomy’s vassal is fond of Cornelia, in a way. She also would be a good match, and thus, a good career move. He is wooing her in not exactly the most charming of ways, and Cornelia is not interested, even if it would maybe offer at least some protection from the assaults of Tolomeo’s.

Cornelia as an unmarried woman is threatened from all sides, she confirms Sesto in his plan for vengeance, and even Cleopatra approves, plotting against her own brother.

Jealousy, hate, a battle, and other hardships have to be overcome, until this initial mess evolves into a happy ending, at least on the surface.The plot isn’t only about power though; what no one could have foreseen is that Cleopatra falls in love with Caesar; and it is mutual.

The production

The production has been called “Jungle Camp in Egypt,” by a newspaper — “Das Dschungel-Camp” is a German reality TV show — but I refuse to be so quick in my judgement. For me, it had upsides and downsides. A quick round-up to start with:

Whenever someone states that something is exactly like something else, it is most probably wrong. At some point, all comparisons fail. The directors, Moshe Leiser, and Patrice Caurier are intelligent, so they know that. Yet, together with Christian Fenouillat, who was responsible for the stage design, they picked a cliché setting to start with, one that makes “Dynasty” seem complex in comparison.

Caesar’s conquest of Egypt is just like some war against a Muslim state? Let’s accept it, for a moment, as a working hypothesis, because this was one of the basic ideas of the Salzburg production. To detatch it a little, maybe, from actual events, it was set back, somewhere around the 70s or 80s, at some date where trousers with their waistbands pulled over the bellybutton seemed to be a great idea.

A comparison as daring as this is bound to break at some point — and the production played with this idea, as far as I gathered. By and by only tropes and quotes were taken out of history, just as Händel and the Librettists, Haym and Bussani did when they wrote Julius Caesar, so, it seems legitimate, after all. Of course, Tolomeo and Ceasar’s relation is somewhat historically verified, but the Parnassus scene at the latest breaks with any historic foundation. Also it is hard to picture the same Cleopatra singing “Caro!” and meaning it with Marc Anthony, and comitting suicide, after she has tested out various venoms of offended snakes on her slaves, calmly observing how they died.

Caesar in this production is a conqueror from the West, supposedly the EU, as a clue in the end is hinting. Actually, during the last 67 years, Europe was quite well-behaved, so this suggests the somehow decent approach that Caesar in the opera in fact shows. He despises people who only know cruelty. He prefers to ask first, he is just the type of guy.

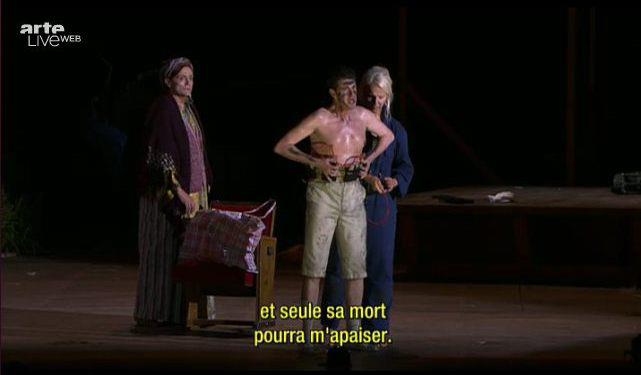

Sesto is staged as an assassin with a background. He is equipped by his mother with a explosives belt even, but all references that could hint religion were left out. I liked it, because after all Religion in this context is never more than just used to gloss over personal motives of hate and disappointment.

The rest of the staging is set in the vague 80s, which means leopard print and high heels in abundance. (Agostino Cavalca as the costume designer is the expert here.)

No hope for humanity

There are two character triangles in the opera worth mentioning. One is Caesar and Cleopatra, with Tolomeo getting in their way, and one is Sesto and Cornelia, again, with Achilla and Curio at times, but again mainly Tolomeo in their way.

The intensity of von Otter’s and Jaroussky’s acting made Caesar and Cleopatra seem like a buffo couple at times. Even more, Caesar and Cleopatra having a good time in the sight of grief is not exactly a sign of empathy, so this enhanced the impression that this was a two-classed society.

The utter hilarity in the Parnassus scene — Cleopatra riding a torpedo while wearing a blonde wig — as well as other scenes made especially Caesar appear somewhat heartless. He only has one aria to show weakness and strength at the same time — his “Dall’ondoso periglio… ” (From the perils of the ocean.) Normally, this and the following “Aure, deh, per pietà,” (Zephyrs, come to mine aid) are some of the most moving moments of the opera. In this production, it didn’t suffice for me, however Scholl’s rendition was a valiant effort.

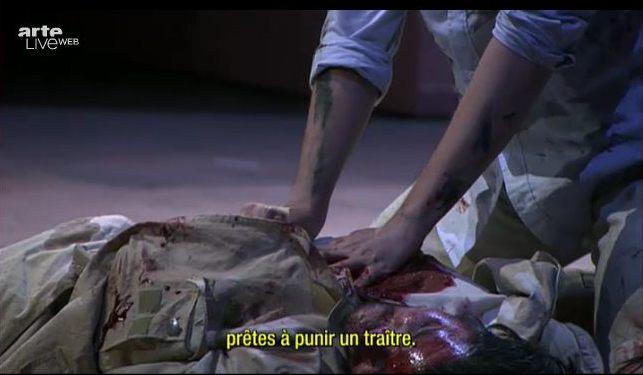

It wasn’t helped by half-dead soldiers crouching in pain at Caesar’s feet in that scene, and where a normal reflex would be to offer fist aid or last rites at least, he just stands there and sings, beautifully though. At the end he is hiding amidst the suddenly very dead soldiers, his face a grimace of disgust when he lies amidst the corpses of the men who died for him.

So, Caesar seems relatively heartless, and it rubs off on Cleopatra’s part; her sudden mood-swings seem staged as well. What in a teenager would just-so pass as charming seems vulgar and shallow; it doesn’t necessarily have the same effect when sung by a queen with a preference for black leather.

A Lot Of Almost-Sex & A Little Sexiness

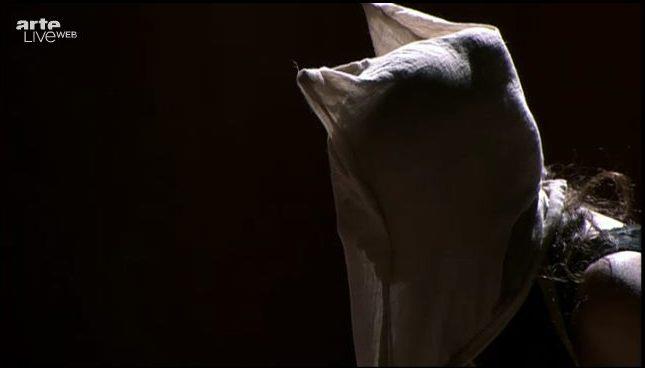

That Scholl as well as Bartoli still managed to shine in their arias is a great achievement; it wasn’t made easy. It is hard to act and transport deep emotions, like in Cleopatra’s two “big” arias — one of which she had to sing with her head inside an environmentally friendly shopping bag — when the scene is surrounded by meaningless actions and substitutes.

Red-headed torpedoes — and to make the symbolism even clearer, with fans held against them to look like testicles — not to mention Sesto’s snake he is handling with a certain skill — the production is full of blatantly obvious symbolisms, and frankly — they are so obvious that they even make a p*rn plot appear subtle in comparison. And what is worse, the directors are right — at least I up to some point enjoyed it. However, body and soul can’t feed on p*rn alone. All this half-rape, half-snuggling, half-w*nking, a lot of leopard print and black leather — but not even a kiss! It all leaves a shallow feeling. It is oversexed and yet all the characters seem to be lacking something.

I like hidden references, guessing games, and food for thought, so, the in-your-face-symbolism disappointed me a little at first. If I wanted to see p*rn, I could have watched it — but I wanted to see Julius Caesar! Single pictures are something else, they are a snapshot that leaves the before and after to fantasy. Just for the record: The sight of Jaroussky snake-wrestling is not to be despised, after all.

To the Parnassus scene: Cleopatra stages this for Caesar, which in turn suggests, again, that he is not someone who would pick up more subtle hints.

What saved the production for me was that by and by though, I have to say, I particularly liked the character of Sesto, and how it was depicted. He was maybe portrayed as the deepest and most complete character of them all, even more so than Cornelia, who in contrast to most productions was staged as a distanced, self-absorbed woman.

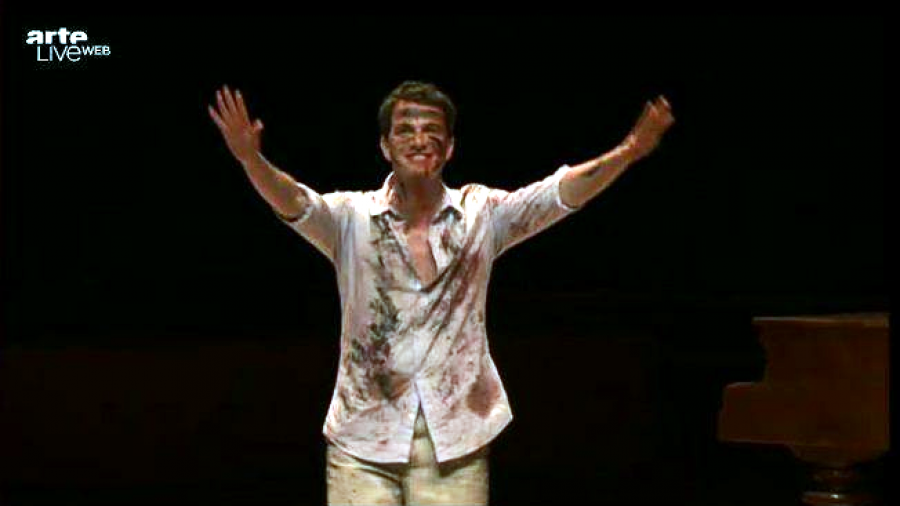

Oh, and we saw Jaroussky shirtless! There, I said it. Of course, Sesto’s absence of a shirt is meant to show his vulnerability, and Jaroussky’s figure helps in transporting this aspect.

So, let’s just continue where I have stopped at: More than obvious symbolisms.

L’angue offeso

My first thought when I saw the pictures from the production was that according to my understanding, if anything, Sesto does not in particular feel threatened by penises. Well, in a very far-fetched metaphorical sense, as Caesar and Tolomeo have an ongoing competition about who is going to rule Egypt, and he is in their way. I am not sure though whether that suffices as an excuse.

Originally, Sesto is not threatened by but in fact compares himself to a snake. He won’t rest until he has brought the enemy down with him. So why was this inversed? I had to think of a Buddha quote there:

Holding on to hatred is like drinking poison and expecting the other to die.

The one thing that is sure, is that Sesto is an instrument; his grief is being exploited, by his step-mother as well as by Cleopatra. It is his duty to avenge his father’s death, according to tradition, and he feels he must oblige. We sense though, that it won’t be the solution to all problems for Sesto, even if it is a very comfortable solution for the others.

But it isn’t even his own hatred alone; His own mother arms him with the assasin’s belt; she is the one who gets more and more detatched from him. Joint hatred can never replace mutual love.

From closeness in the beginning, they have at first Achilla literally standing between them, until it is armies, worlds, and generations. The meeting at the final chorus is bitter. They are standing next to each other, just like strangers.

I know people who have killed — at war, but it doesn’t matter. It changes people, you won’t ever forget. The ending shows, Sesto will never forget either. He still has his battle-worn shirt on, whether his mother has peeled herself out of her shabby garments to reveal a robe fit for the occasion.

That Sesto is accepted by Caesar and finds himself in the middle of the partying adults behaving like teenagers really, smoking joints (Cleopatra forgot to light hers, by the way,) and drinking, for me symbolizes he is now part of the establishment. However, he is not like them. He has maybe the deepest feelings of them all, and no one can help him to handle.

A wasted soul, and a wasted youth. Smile? Whatever you say. It seems to be a good solution. Just smile, and nibble at the titbits being offered. Sesto’s smile is horrible to watch, and that Tolomeo whom he has killed joins him is no relief — Sesto has finally crossed the brink of sanity. Tolomeo is something only he can see at this moment. The scene made me despise Caesar and Cleopatra flaunting their happiness.

What is left for Sesto? There is no target for his hate anymore, and it doesn’t take very profound psychoanalytical skills to deduce that this was the only thing that kept him going. He has no purpose now any more. What will he do? Suicide, maybe. His step-mother is no help, she doesn’t attach, as little as she cares about his shabby clothes, when everyone else is dressed appropriately for the final celebration.

Cara speme

I want to share one aria in particular, the “Cara speme.” Even before Jaroussky started to sing, I was taken. This must be one of the most hopeless “Cara speme”s ever, I thought. The phrasing is not something smooth and uplifting, it rather pictures a timid effort, the non-legato makes it sound despirited.

The aria is set in scene with Sesto preparing himself for battle. It hurts to see him camouflaging himself, as of course the sullying is more than just a physical act. The motive will be enhanced later, when he will smear himself with Achilla’s blood — I will come to blatant symbolysms later on.

Something is being spoilt at this aria, or already has when the aria starts: Innnocence. Children shouldn’t wear weapons. There is no more the innocent hope of a child when the aria starts, only its fragility. Jaroussky starts out the aria in the most boyish of voices — utterly heartbreaking. In the Da Capo he manages to give every embellishment a meaning; even the accompaniment softens up, his voice is getting more lush and flexible; it gains more colours, and is becoming even more beautiful and complete, and by and by a feeble but true hope shines through. It doesn’t make it less heartbreaking, however. We know that this is a boy who has just gotten hold of a Walther P99, who thinks that with this he can handle professionals armed with MP5s.

For me, the “Cara speme” was the best part of the night. Superb in every way.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=GlhgqEQjXe8

Thank you @mutewoman for being so quick!

SESTO

Cara speme, questo core

Cara speme, questo core

tu cominci a lusingar.

Par che il ciel presti favore

i miei torti a vendicar.

Pet Peeves

- Blank ammunition won’t even kill a snake.

- We blame the directors for not being able to get Dynasty as well as Elvira out of our heads while watching.

Venere bella …

- And finally: Scholl topping Bartoli? You must be kidding.

On Our Own Behalf

Thank you for visiting our Facebook wall and for sharing your emotions during the broadcast, via chat and in comments, a big thanks for your participation, submissions, and help.

Picture credits

The images used in this post are all screen grabs from the Arte livestream, in low resolution. If you are the copyright owner and object to your pictures being published on this site, ask us to take them down, and we will comply immediately.

The production is still available on Arte’s web page.

This step towards Sesto´s madness would have been a very poetic end for the character, but not only Ptolemy is alive but also Achille invited by Curio. Sorry.

Hm, I disagree, and no need to be sorry about that — thank you for your comment!

They both should be dead, in the opera as well as in the production, of course. I doubt that Curio invited Achilla, it all may be a trick of Sesto’s mind. Achilla gave Sesto the seal to command his armies in the libretto, so they have more of a connection than Achilla would have with Curio.

*edit – I just re-watched that part.*

Why Achilla is there … Sesto more than just saw him dying. He still has his blood smeared on his shirt. That Achilla stands next to Curio must not be proof he is actually there for him. They greet each other as equals which they somehow are in status, but not as friends.

The presence of the dead makes the scene surreal, at any rate.

I like the idea more that they are only there for Sesto. Another possible explanation would be it is there to symbolize that Caesar and Cleopatra even forgive their dead enemies. However, forgiveness as a major character growth as proof that the emperor is worthy, this more fits “La bontà in trionfo”, another showcase-piece for Bartoli. The final party has nothing noble about it whatsoever the way it is set in scene.

I would be delighted to hear different theories!

[youtube XB5vmJ8jFs4]

Ah! signor, s’è ver che in petto

Qualche amor per me serbate,

Compatite, perdonate,

E trionfi la bontà.

I love your review and I agree with you on almost everything, but I think when you speaking of intentions more or less intelligent staging of Leiser-Caurier, is putting into the minds of these two stage managers their own ideas and in their hearts their own sensitivity.

I do not for a moment that this staging of “Giulio Cesare” can be interpreted in a way so deep and subtle.

Except that it Leiser-Caurier they are enemies of Caesar and Cleopatra or feel personal antipathy by Bartoli and Scholl, you can not understand a stage so ugly, vulgar, confused and largely borrowed hundreds of operas of the last 20 -25 years. Horrible.

However, it is true that all interventions of Philippe, and Philippe and von Otter, are treated very exciting, very symbolic and a very strong sense of tragedy. But I tend to think that all these scenes are wonderful because Philippe is, and puts in its interpretation all his talent, his sensitivity, his body and soul. Thus, it is very easy to create a masterpiece on of anything.

If Sesto had been any other countertenor, “Svegliatevi” (with that outfit) had touched the parody and “L’aure che spira” had not made the tears of any viewer. But Philippe was Sesto, and the mixture of fear and determination, of helplessness and daring, was breathtaking.

I would also like Leiser-Caurier have thought in the state of confusion and terror that is the character at the end of the opera, but it was you who has thought and has seen and you have been generous enough to assigning it to them. In this production, the merit of the depth and beauty of Sesto is to the music of Handel, Philippe and you, Lankin.

First of all, what you said is very flattering, and it took me a little to take this in. Thank you very much for the praise 😉

The thing is, of course it is all about our perception. Think about a clue in a crime novel that is not red herring. Has it been placed there deliberately, so we can guess the murderer, or was it just a subconscious lapse of the author, or something he only decided that would gain importance later on?

Of course there are some basic guidelines to judge a good author or a good story by. The problem with directors and productions is — it is close to impossible to leave the performers out of it. (They even make the latest Bayreuth Ring production almost bearable.)

Cruel to lay your daughter on a euro-pallet …

Ant then there is the perception of the viewer, and a great deal is on the recipient’s side, as we all mingle the production with our own background and nature, and no two people are completely alike.

So, even if I try, I cannot leave myself out, and I try to stick to the guideline: benefit of the doubt. Bartoli wanted those directors, apparently, and it got me thinking why. Apart from one oddly photoshopped cover picture of a CD of hers I can see no flaw in her judgement.

image credit: “Sacrificium,” booklet p. 27.

Just a theoretical question: It is okay to photoshop Bartoli without her female features, why is it not alright … but I digress.

But even taken this into account, I can’t get warm with this production, and I would like to read some background about what they meant to say.

The staging felt and looked fake, starting at Pompeyo’s head. This, and of course the intestines that Tolomeo has a belated lunch on look like B-movie-props. The Caesar of this production likes B-movies, as Cleopatra can confirm — her Parnassus scene there is a complete success. Okay, so I took it for a fact: This Cleopatra is after power, money, and a little love, and Caesar wants the same. A perfect match.

However, this approach for me prevents to feel with those characters. This is my main problem with the production.

Even if my favourite character was always Sesto, since I first got in contact with that opera, I liked the others as well. And, what is more, Händel loved them, all of the main characters, so he gets them to show many different sides. Cleopatra — the playfulness (and bitchiness) of a 16y-old with the “Non disperar”, deep emotions, the greatest joy, and planfulness – Everything that classifies her as a true queen. If this is cut down to just planfulness and bitchiness, it is a little meagre.

The Caesar of this production I wouldn’t even trust with the management of a swingers club (a job he might in fact like to have), let alone an empire.

A reduction of Caesar and Cleopatra in that way runs against my grain, as for me it seems to contradict Händel.

The scene how it was evolved around Caesar’s and Cleopatras arias, especially, hurt me. For me, the “Aure, deh per pietà,” as well as Cleopatras “Se pietà” deserve a frame of peace and seriousness. There is no lie in them, and no staffage, they are just as honest as Andronico’s “Benchè mi sprezzi”, e.g.. In the production however, they appear false, and this is what annoyed me most. (Bartoli almost saved hers, despite the shopping bag.)

What I personally did not like about the way Sesto was staged, was that he was often portrayed as utterly helpless, and more, defeated, and very early. He has no chance by himself against his opponents, only later, when he has allies — or people who use him, with this I am d’accord. I find his character heartbreakingly tragic. But to give him blank ammunition that sounded like it was something that made him seem ridiculous, also his backjumps at his shooting. It more seemed like a stereotype girl afraid of a spider than a boy about to shoot a snake at times. (Of course it would be blank ammo in theatre, but there are different solutions. Ask the stage director of “Elektra” in Stuttgart who successful spoilt the Orchesterzwischenspiel with it for advice.)

So …

Yes. /signed.

Forgive me, Lankin, I do not know English, and the Google-translator is my friend and my enemy.

Although much effort has cost you understand what I said, I think everything I’ve written about you. And about Philippe.

I’m sorry this reply to a little longer — there is nothing to be sorry for! I never would have guessed your post was aided by Google translate to a significant degree either, so you underestimate your own skill, I guess 😉

But at any rate, feel free to comment in any language really, as long as you feel comfortable 😉 Biri’s the one for Spanish, Italian and Catalán, Bunny for Chinese, French, and a few language skills she is hiding from us.

This one was in Spanish, from Biri:

http://www.philippejarousskyfans.com/2012/03/21/gran-teatre-amb-philippe/

So, no holding back 😉

About Cesare and Cleopatra: you complain that they are not made to look like pleasant characters, but rather as a nasty duo of powerhungry bastards. But that was exactly the case with the historic Cesare and Cleopatra! After Caesar died, Cleopatra seduced Marcus Antonius, and after he died, she tried her charms on Augustus as well, but apparently she was not his type, because he refused. Only then did she kill herself. Liz Taylor did a fantastic movie, but that was waaaaaay besides the truth!

The historic Sesto was also everything but a bashful youngster taken advantage of, by the way. Far from it! But I could never see Philippe portraying him like he really was, I am afraid…so let’s keep this Sesto in our hearts as basically a sweet kid. He did that great.

[…] as a stream from the Pfingsfestspiele; to see it live was something entirely different still. As I wrote down my opinion on the staging before, I will now focus on the singers, and the performance of that […]